There are questions that, however uncomfortable they may be, need to be asked. At Alma, we believe that a true commitment to education not only involves supporting others, but also daring to question, facing challenges head-on, and opening spaces for change. In 2025, together with the directors and teams of the Juan Misael Saracho Teacher Training Schools in Tarija and Clara Parada de Pinto in Beni, we have decided to take that step. And we have done so with the conviction that asking ourselves honest questions is the first act of responsibility for improving the training of those who will one day lead our classrooms.

This year, we have initiated two research projects that touch upon the educational process. At the ESFM in Tarija, we focus on the quality and relevance of the research products produced by students within the framework of the IEPC-PEC. These works are not only the result of years of training; they are also pedagogical proposals that reach educational units and, in the best of cases, could transform classroom teaching. But are they fulfilling that purpose? Are they useful, applicable, and contextualized? Do they truly help solve the problems faced by the schools they serve? With this research, we seek answers that will allow us to adjust assessment criteria, strengthen educational support, and ensure that research products are not just a graduation requirement, but a true contribution to the education system.

In Beni, on the other hand, the focus has been on the professional future of ESFM graduates. Since 2019, hundreds of young people have graduated from this school, many of them from other departments, attracted by the greater employment opportunities. But how many actually stay in Beni? Under what working conditions? Are they working as teachers? What training gaps do they identify once they face the labor market? And, in parallel, how can we explain the high rates of teacher vacancies that recur each year in the schools of this region? Through direct contact with graduates and district authorities, this research aims not only to understand a complex reality, but also to generate concrete proposals that can inform institutional decisions, such as the opening of new programs or the redesign of training plans.

What distinguishes both processes is not only the critical approach or the technical value of the research, but the genuine commitment of local authorities. In Tarija, the IEPC-PEC coordinator has taken an active and deeply involved role. In Beni, the general director has opened doors, shared data, and encouraged the team to go further. In both cases, trust has been the key. They have shared internal, confidential information with us, knowing that our interest is not to point out errors, but to build solutions. And they have done so because, like us, they believe that the education system can improve if it begins with an honest, rigorous, and humane approach.

We hope to complete both studies by mid-November and publicly share their results in each department. This will be an opportunity not only to present findings, but also to mobilize support and generate new conversations. Because if this journey has taught us anything, it’s that change doesn’t begin with certainties, but with courageous questions.

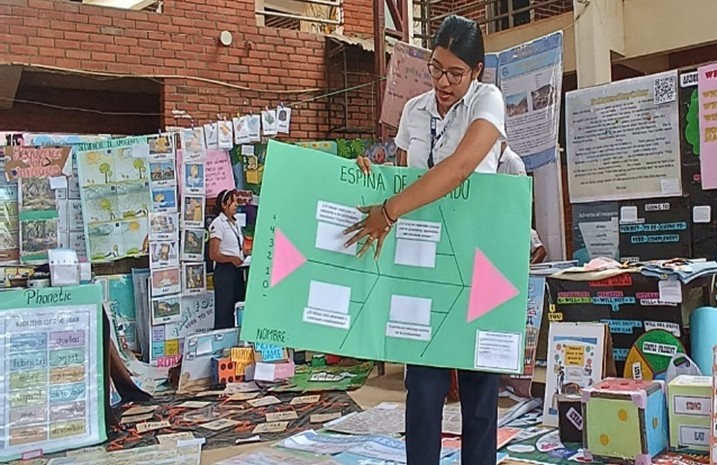

Fifth-year ESFM student in Beni. Presentation of materials that will be used at the IEPC-PEC